Every evening, just before bed, Josephine Mundava checks her phone, not for messages, but to see where the “Shangani Wanderer” is. The young white-backed vulture, fitted with a tracking tag as a nestling on Shangani Ranch in Zimbabwe, has become a symbol of hope and survival in a region shadowed by poisoning incidents and poaching.

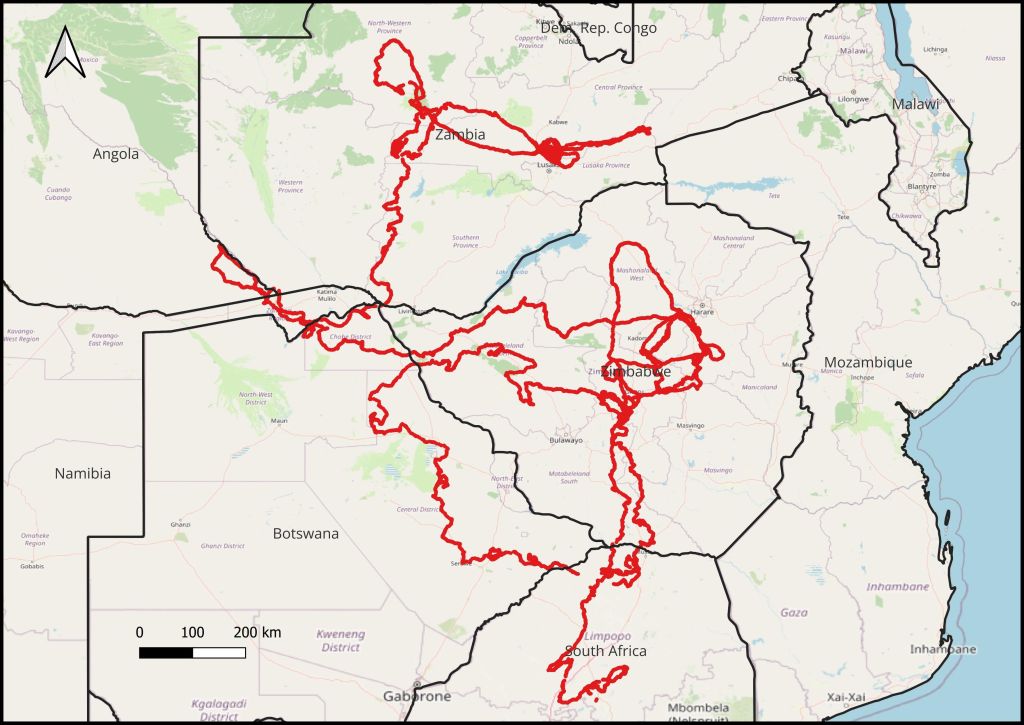

“Yes, the Wanderer is still safe,” she says with cautious relief. “This morning, it was in Kafue National Park in Zambia.” Earlier in the week, it had been on the Angola-Namibia border. “It moves a lot.”

Mundava is a lecturer at the National University of Science and Technology in Zimbabwe, and, together with her post-graduate students, researches and monitors the vulture numbers and breeding habits at Shangani.

Concern over the welfare of the Shangani Wanderer, and vultures across the region, has heightened following the poisoning of 100 of the birds in the Lionspruit Game Reserve near Kruger Park in May. This massacre followed weeks after 100 vultures were killed and 84 rescued after being poisoned in the Kruger National Park. In both cases, white-backed vultures, already on the critically endangered list, made up the highest number of deaths.

The deaths are often deliberate, as poachers poison carcasses to kill birds whose presence is erroneously believed to give away poacher activity, or collateral deaths when poachers poison animals such as elephants for their tusks. Furthermore, vultures are also killed for cultural and muthi reasons.

Of the eight vultures tagged at Shangani so far – three in 2023 and five in 2024 – one dropped off the radar, in Namibia in September 2024. “We don’t know what happened,” says Mundava. “The tag just stopped transmitting, in the Chobe reserve in Botswana. We haven’t been able to retrieve it.”

The Wanderer was one of two vultures tagged in the nest on Shangani Ranch, at the end of November 2024. It wasted no time exploring the southern African landscape after it took wing, says Mundava, heading west across Botswana with stopovers in South Africa.

“With wingspans reaching 2.3 metres, these magnificent scavengers typically begin their independent journeys around 120 days after hatching,” says Mundava. “Our data shows Shangani Wanderer has already traversed international borders, demonstrating the critical importance of transboundary conservation efforts.”

White-backed vultures face numerous threats including poisoning, electrocution, and habitat loss. Their rapid decline has earned them “critically endangered” status, making this satellite tracking project vital for their protection.

Tracking such individuals gives scientists a rare chance to follow a bird’s journey from fledging through its wide-ranging forays across southern Africa.

The broader tagging project, sponsored by Oppenheimer Generations Research and Conservation, was born from a need to understand how vultures use landscapes -protected areas, private ranches, and communal lands – amid growing threats. The Shangani vulture population itself has grown from about 10 nesting sites in 2012 to an estimated 80 to 100 today. “Some areas aren’t easily accessible, so that’s a rough estimate,” says Mundava.

Because monitoring every nest isn’t feasible, the research team uses satellite tags to track select individuals and build a picture of how vultures navigate southern Africa’s complex landscapes. Patterns are already emerging. “Most birds spend a lot of time in protected areas -national parks and private reserves – and some come back to Shangani regularly,” she says.

This raises the question: how do vultures “know” where it’s safe? “They don’t,” she laughs. “They follow food. What we call protected areas often have better wildlife management, and more carcasses. That’s what draws them.”

One of the birds being tracked, for example, nests in the Tuli region along the Zimbabwe-Botswana border but regularly returns to Shangani, likely for feeding. “If there’s a carcass, they’ll show up on the map, then disappear again,” she says.

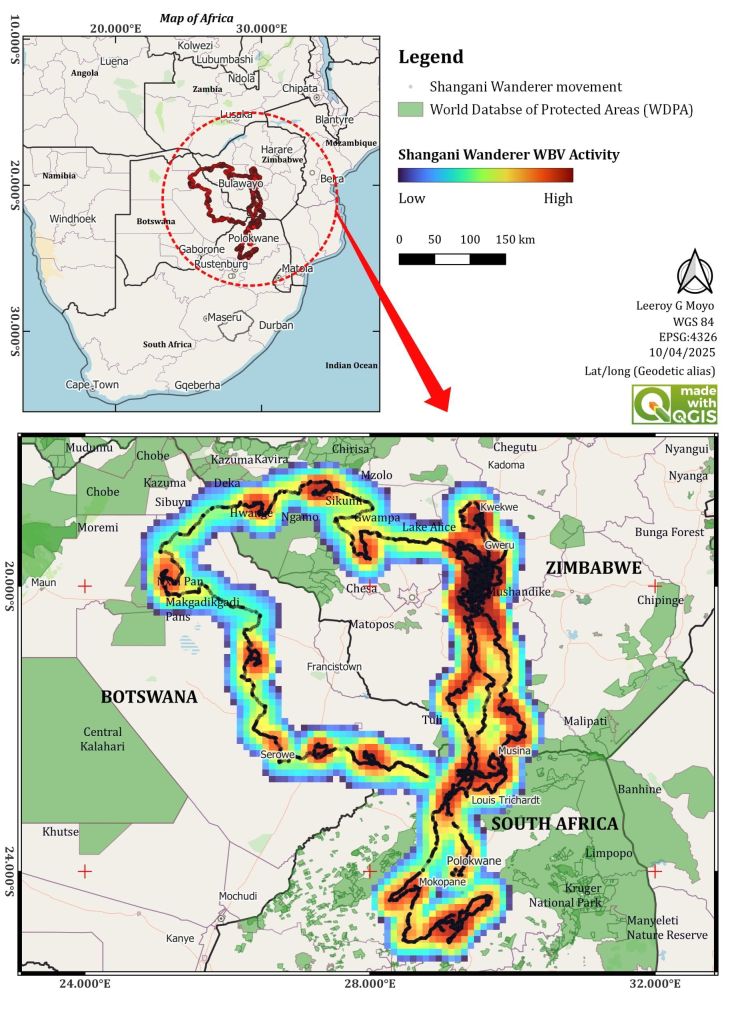

Now, a Stellenbosch University honours student is analysing the movement data in greater detail, looking at habitat use, land types, and foraging hotspots. “When vultures feed, they often stay in one place for a while. So we can create heat maps showing their favourite feeding grounds.”

Though the team can track where vultures go, they don’t always know what they’re feeding on. “There’s someone starting a PhD in Hwange who will look into that,” she says. “It’s a long-term project. But for now, with the Wanderer, we’re just seeing movement patterns.”

Vultures tend to be opportunistic, though carcass size matters. “Larger carcasses attract more birds. Small ones might not be worth landing for,” she explains. “But in terms of species, we don’t know if they’re picky.”

The Shangani ranch has provided fertile ground for student involvement. Each year, Mundava is accompanied students, whose projects have included studies on community attitudes toward vultures, lead contamination in birds, and basic breeding patterns. “When we tagged birds, we also collected blood, feathers, and bones to test for lead exposure,” she says. Results are expected soon.

Lead poisoning occurs when vultures feed on carcasses left behind by hunters. “Bullets fragment and leave tiny pieces throughout the meat,” she explains. “Even when hunters cut out the wound channel, fragments can be far beyond it. If vultures ingest them, they’re at risk.”

But lead isn’t the only danger. Vultures across southern Africa have increasingly fallen victim to poisoning, sometimes deliberate, sometimes incidental. “The reasons are diverse and hard to predict,” she says. In Zimbabwe’s worst incident, 183 vultures were killed in 2013 at Gonarezhou National Park, near the border with Mozambique. “It was an elephant carcass laced with poison. The tusks were gone, and the vultures’ heads were cut off, likely for rituals.”

Other cases, like the cyanide poisonings in Hwange, are more straightforwardly tied to elephant poaching. “In those, nothing was taken from the vultures; it was just collateral damage,” she says. “But it’s very difficult to prosecute. Poachers are usually long gone by the time carcasses are discovered.”

Legislation has toughened since then. In Zimbabwe, the maximum sentence for vulture-related crimes is now three years. “It used to be just months,” she says. “Now there’s more advocacy and stiffer penalties.”

Unfortunately, white-backed vultures, the species to which the Wanderer belongs, are among the hardest hit. “They’re the most abundant, so they arrive in the largest numbers and suffer the most in poisonings,” she explains. “They’re also critically endangered.”

Still, it’s not all grim. The tracked birds provide rare insight into just how far vultures travel. Mundava cites one bird, which they tagged at Shangani at 3 in the afternoon, but by nightfall it was already in Gonarezhou, over 400 kilometres away in a straight-line distance. “They cover huge areas,” notes Mundava.

Mundava checks her phone to give an update on the tagged vultures. The Wanderer is in Kafue National Park in Zambia. Another bird is in Angola, near the Caprivi Strip. One remains in the Shangani region; another hovers between South Africa and Botswana. Another pops up in Zambia. “They seem to like Zambia and Namibia,” she says.

Every ping from a tracking tag is a sign of life, and a small reprieve from the constant worry that another might go silent. For now, the Wanderer flies on, following the invisible threads of thermals and food, and watched, always, from below.

Yves Vanderhaeghen writes for Jive Media Africa, science communication partner of Oppenheimer Generations Research and Conservation.