Yves Vanderhaeghen interviews semiochemist Dr Peter Apps, who wants to use animal smells to keep them safe.

Predators and humans don’t mix well. Each in their own way wreaks havoc on the other. The solution lies not in bullets, fences, or poison, but in chemistry, according to Dr Peter Apps, a specialist in how animals communicate through chemical signals.

While he won’t say that he has found the silver bullet that will put an end to human-predator conflict, he believes he has a “revolutionary” solution.

Dr Apps runs Botswana Predator Conservation’s BioBoundary Project under the Wild Entrust Africa umbrella, which is finding ways to mitigate the conflict using artificial equivalents of natural chemical signals to keep predators away from livestock, or safely inside wildlife conservation areas.

“All mammals communicate via the chemicals in body odours, secretions and scent-marks,” says Dr Apps. The signals coded by the chemicals in territorial scent-marks offer a new way of keeping predators away from livestock, and out of areas dominated by human development.

He says that a lack of practical alternatives makes killing predators the default solution for farmers whose livestock are being preyed on, and that this lethal control “is the main threat to predator populations worldwide”.

The stakes are high because both are fighting for survival. According to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), “every year, hundreds of humans and thousands of animals die due to human-wildlife conflicts. Habitat loss and in some instances conservation successes combined with an ever-increasing human population has resulted in humans and wild animals living in closer proximity and sharing the same scarce resources.”

CITES also points to the complexity of the situation, as, even though “the conservation of animals is an important global good … the reality is that those living with wildlife usually carry the cost associated with this conservation imperative, including loss of income, essential crops to support their livelihoods and tragically sometimes also loss of human life”.

Dr Apps too, emphasises, that “predation on livestock is a direct threat to rural livelihoods, which traps small owners in an ecologically and economically destructive poverty spiral and inflicts direct costs on the large-scale commercial livestock industry in South Africa of R1 billion a year”.

He cites some examples from his own research on the impacts of predators on subsistence livestock farmers in northern Botswana over the past 18 months: 103 livestock were killed in 49 lion attacks; 21 livestock were killed in 17 spotted hyaena attacks; 57 livestock were killed in 10 jackal attacks; 23 livestock were killed in seven African Wild Dog attacks and nine livestock were killed in five leopard attacks.

The backlash from humans is threatening predator populations, which in turn is disrupting the ecosystems that they help to keep in balance. The long-term impact extends to humans through the environmental degradation that results from lethal predator control.

Human-wildlife conflict is not just about livestock deaths. Humans, it should be remembered, can be prey themselves. “Where predators’ habitat and natural prey have been replaced by domestic animals and dense human populations, as in India and Nepal, predators kill thousands of livestock and hundreds of people every year. “For example, in one district in Nepal, they lose an average of six children annually to leopards. India is on a similar scale in areas where there are leopards. There is huge potential in such areas for using chemical repellents to save human lives.”

Dr Apps runs the BioBoundary Project from the Botswana Predator Conservation Wildlife Chemistry Laboratory in Maun in northern Botswana, which he describes as a “dusty little town at the end of the tar road” but which the tourist brochures call “the tourism capital of Botswana” and “the jumping-off point for the vast inland Okavango Delta”.

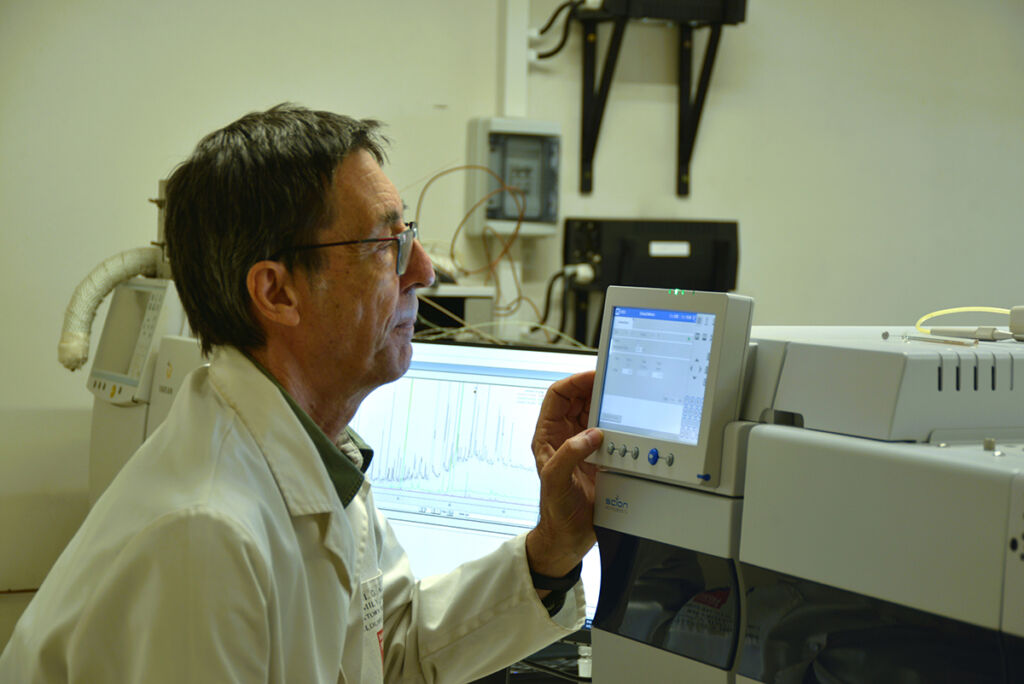

He equates the project to “natural product drug development. We are bioprospecting for the chemical signalling components of predators’ scent-marks”. The crux of the work lies in the integration of cutting-edge fieldwork on scent-marking behaviour with world-leading chemical analysis of predator scent-marks using gas chromatography – mass spectrometry, a technique which can put a chemical name to a billionth of a gram of a volatile organic compound.

“Mammal scent secretions contain thousands of components, but the vast majority of them are just metabolic waste products with no role in communication. We focus on the signalling compounds, where the challenge is to identify which chemicals code which signals, and most importantly which ones say ‘Keep Out’. To dig these signalling needles out of the chemical haystack, we integrate detailed observations of carnivore behaviour from Botswana Predators Conservation’s field research work with the analyses in the lab”.

BioBoundaries was conceived to protect endangered African wild dogs by Dr J.W. “Tico” McNutt, a director of Wild Entrust, the umbrella organisation for the Botswana Predator Conservation Programme. Wild dogs, also known as Painted dogs, compete with other large predators such as lions and spotted hyaenas and naturally exist at low population densities even in large, protected areas.

Only about 6 600 currently survive in the wild, and when they stray outside the boundaries of wildlife areas where they are protected, they are vulnerable to lethal control by livestock owners, and road fatalities. To address this conservation challenge, the wildlife chemistry lab was set up to identify the critical compounds and produce a synthetic (artificial) territorial boundary scent that would help keep wild dogs inside the relative safety of protected areas.

“When the BioBoundary project was started in 2008,” says Dr Apps, “there were still big gaps in what we knew about wild dog scent marking. We knew that packs had to be communicating by odours in urine and faeces, but not how they do it – how do packs that range over hundreds of square kilometres even find one another’s scent marks? In 2015 one of the BPC field researchers spotted a pack investigating and scent marking the exact spot at a road junction where a dispersing group of wild dogs had been seen scent marking 10 days before. They realised that this might be significant, and we put camera traps at the spot and discovered that four neighbouring wild dog packs were using that same scent marking spot – an area only 15-20 metres wide, in territories 10-15 kilometres wide. These tiny spots at the scale of wild dog movements, where they leave scent messages in faeces and urine, and read the messages from their neighbours became known as Shared Marking Sites. We soon discovered that dispersing wild dogs also go to these shared marking sites to leave their scents – like Tinder profiles and pick up profiles from other wild dogs who are thinking of dispersing and forming new packs. These marking sites are the hubs of wild dog communication networks, and their discovery in 2015 was the critical breakthrough in understanding the biology of African wild dog scent communication”. “In 2019, with funding from the St Louis Zoo WildCare Institute, we expanded our camera trap surveillance to 22 wild dog marking sites, and we have captured hundreds of videos of wild dogs scent marking in our study area. As a result, more is known about African wild dog scent marking than about any other predator.”

The BioBoundary Project’s initial focus on keeping wild dogs inside protected areas expanded into developing repellents to keep predators such as leopards and spotted hyaenas, which already live outside protected areas, away from livestock. To do so ran counter to an orthodoxy within the science of semiochemistry (the study of chemical communication). “Mammal semiochemists had talked themselves into believing that mammal chemical signals were all irreducibly complex, that they require all of the hundreds of components of a scent to be present in particular ratios, and if anything is missing then the chemical message is unreadable.

There is zero evidence for that belief, but it seriously hampered practical applications of mammal scent signals, because replicating a mixture as complex as a mammal scent is technically and financially impractical.” One of the BioBoundary Project’s major scientific breakthroughs has been “unique demonstrations of wild predators responding to single compounds in the same way as they do to natural scent-marks, which disproves the claim that scent signals are far too complex to be replicated. We have also demonstrated that responses to single compounds increase with the rate at which they are released, giving dose-response curves which are unprecedented A compound we identified in wild leopard urine; 3-mercapto-3-methyl butanol (3M3MB), deterred leopards from entering a cattle ranch, protects kraaled calves from leopard predation, and deters spotted hyaenas from crossing a fence intended to separate wildlife from livestock.”

Dr Apps recounts examples of the effectiveness of 3M3MB as a leopard repellent. On a cattle ranch that previously used lethal predator control, camera trapping at a cattle kraal for four months without 3M3MB captured seven leopard videos and one calf was killed by a leopard, and when 3M3MB was used for 4.5 months, no leopards were caught on video, and no calves were killed.

A subsistence cattle post owner reported a leopard at his calf kraal on four consecutive nights, and after 3M3MB repellent was deployed the leopard did not return. At a third site, leopard predation was reduced by 85% compared to when there was no repellent present, which translates into 11 calves, worth R75 000, saved in 17 months.The value of the livestock saved by using a chemical scent repellent was at least six times more than the cost of the repellent”.

In addition to 3M3MB for leopards and spotted hyaenas, the BioBoundary project has a long list of compounds with positive results in screening tests already queued for real life testing on jackals and caracals, the two most serious predators of small livestock.

With the help of a substantial grant from Oppenheimer Generations Research and Conservation in 2022, Dr Apps expanded the real-life efficacy testing which demonstrates the viability of the BioBoundary concept as a wildlife management tool. “We are screening compounds on a wildlife conservancy and running real-life efficacy tests on two cattle ranches and in a subsistence cattle post area near Maun, where human-predator conflict is rife because it borders the wildlife management areas of the Okavango Delta. We need to be working where it matters – where the conflict actually happens. As we speak, there is a pride of lions playing havoc with the cattle just outside the buffalo fence in the cattle post study area, but, sadly, I don’t yet have a repellent for lions.”

Dr Apps emphasizes that “BioBoundary repellents will be a breakthrough in conservation practice, that can be applied to human-predator conflicts all over the world, and if the necessary resources are invested, we can develop low-cost repellents based on chemical signals to provide technically straightforward, economically viable tools to protect both livestock and predators”.

“If we want subsistence pastoralists to use non-lethal methods to protect their livestock, without continual interventions from foreign-funded NGOs, then the non-lethal methods will have to be cheaper and easier to use than bullets, snares and poisons. BioBoundary repellents are the only anti-predation intervention that is at all likely to undercut the cost of lethal methods. Once the formulas for the artificial chemical signals have been worked out, repellents can be mass produced using the same technologies as for insect pheromones, which are used at large scale in integrated pest management. Production, distribution and retail sales can be integrated into local economies, at a cost that end users can afford and that is much less than the value of the livestock that the repellents save from predation.

“If repellents are used in big commercial livestock operations, as in South Africa, the economic arguments are compelling. The direct cost to the South African livestock industry due to predators is about R1 billion a year. “If repellents reduce that by 10% – and our pilot trials suggest that reductions will be closer to 80% – , that will be a saving of R100 million, using repellents that cost R10 -20 million. Those cost to savings ratios definitely make repellents a viable commercial proposition.”

Given the complexity and rapid growth of the challenges to the conservation of predators, Peter Apps is deeply concerned by the lack of innovation in conservation research and that it is problem- rather than solution-focused. “Current interventions are not working as well as they need to – if they were working, we wouldn’t still see predator populations declining. We don’t need to know in any more detail how bad the problem is, we need interventions that actually work, and that are sustainable.”

He uses the “burning house” analogy. “When your house is burning down, you don’t need people to measure how hot the fire is, you need people to throw water on it. But in nearly all of the wildlife research connected to conservation, people are measuring the temperature of the burning house; asking how fast is this species declining? How much has its range disappeared? How much conflict is there with people? How much is it suffering from climate change? These questions are all are about measuring the problems rather than developing solutions what we need is new tools, and new solutions.”

It is clear that innovative research and development like the BioBoundary offers a practical solution to a real problem: “As the evidence accumulates, chemical by chemical and species by species, there is no escaping the conclusion that the paralysing pessimism about our ability to decipher mammal chemical signals, and put them to practical use as management tools is unjustified; that mammals do respond to single chemicals and simple mixtures, and that, if the necessary resources are invested, we can develop repellents based on chemical signals to provide technically straightforward, economically viable tools to protect both predators and livestock.

Wild Entrust’s BioBoundary repellents are currently still at the proof-of-concept stage. To roll them out at large scale and commercialise them is going to need a good deal more research, innovation, and development. For that research and development to happen will depend on the BioBoundary research getting the financial support it needs.

Yves Vanderhaeghen writes for Jive Media Africa, communications partner of Oppenheimer Generations Research and Conservation.

Author

- Tracking the Shangani Wanderer - June 18, 2025

- Rescue, rehabilitate, release: tracking the comeback of South Africa’s pangolins - June 18, 2025

- Fewer weavers, fewer homes: why nest builders matter in the Kalahari - June 17, 2025

Additional News

Pangolins are elusive and heavily trafficked. At Tswalu, researchers are working to uncover their secrets and aid conservation.

Declining Sparrow-Weavers may threaten other birds that rely on their old nests for shelter.