Image credits

Wakefield cattle - Michelle Tedder.jpg

By Yves Vanderhaeghen

“We’ve had a major breakthrough in the Rising Star cave system,” says Professor Lee Berger, one of the world’s most prolific human fossil finders. “We’ve been on an expedition for the last six weeks,” he says, and he is about to go back for a week as we do the interview. His Twitter post makes it clear he’s bursting with enthusiasm: “it’s as exciting as 2008, 2013, 2020 and the last 5 weeks!” For a palaeontologist who has made some of the most significant fossil finds of the last three decades, including Australopithecus sediba in 2008, something extraordinary has clearly happened. “The discoveries we’ve made were right in front of our eyes, they’re extraordinary”, but he’s not letting on yet what he’s found or what it means. “I’d have to kill you if I do,” he jokes.

Perhaps he’ll be more forthcoming at the 11th Oppenheimer Research Conference held in October 2022, where he will deliver a presentation entitled “The Future of Exploration in the greatest age of exploration” .

Meanwhile, he “pleads the Fifth” when I probe whether the new discoveries have to do with Homo naledi.

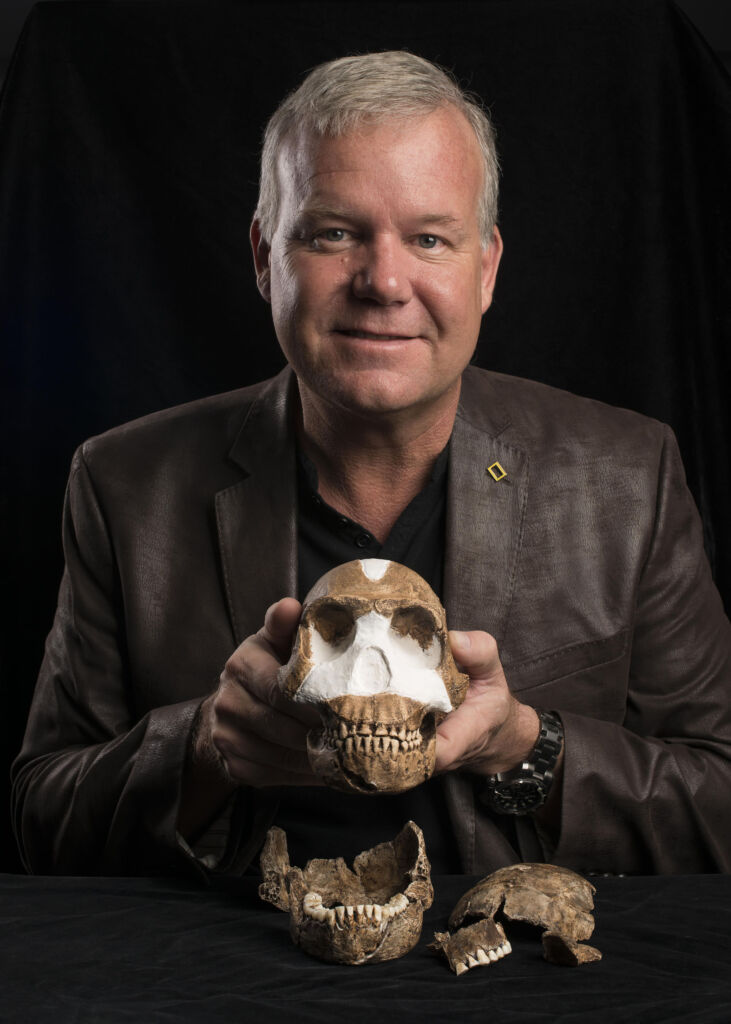

Homo naledi is the name given a new human species which emerged from history due to a bountiful find of more than 1500 fossil bones in the Rising Star cave system in Swartkrans in the Cradle of Humankind World Heritage Site, west of Johannesburg. The discovery by Berger and his colleagues in 2013 and 2014 was the largest such find ever made in Africa, and the fossils, which show both modern and archaic characteristics, have completely shaken up the human origin story and our understanding of our lineage. Since that first expedition, they have nearly doubled the number of individual fossils found, and, says Berger, there is so much more to come as they keep analysing the find.

Describing himself as a “messenger from the past”, Berger says that this discovery destroyed the preconceptions of a progressive, linear development of humans from apelike ancestors to what we are now. H naledi is now dated at between 236 000 and 335 000 years old and was therefore a contemporary of homo sapiens at that stage, which proves that a small-brained hominid was living side-by-side with its large-brained cousin, who is supposed to represent the apotheosis of sentient beings.

Professor Lee Berger with Homo naledi

Berger says he knew that H naledi represented a “radical change in understanding from the beginning, even if at first, I did not know what it was. First, there was the jaw, and that was clearly very strange. Then came more. There was no context then. It would take science over two years to understand what it was. What naledi has taught me is to expect the unexpected. We as scientists and explorers often walk in with enormous preconceptions, based on the history of science and the chance order in which discoveries were made. Naledi is teaching us to throw preconceptions out the window. It is telling us that most of the understanding we have of human evolution is probably wrong. There was no inevitable progression to the large brain which allows humans to be complex. Until this discovery, we thought everything in South Africa had been done by H sapiens in that time period. But that is not true. The big brain is likely not there for what we thought. Naledi was clearly extraordinarily complex, and it seems to have figured out how to be complex alongside humans in those times. It survived alongside Homo sapiens. We have not untangled the data yet, and we are working against hundreds of years of preconceptions”, including about the superiority and inevitability of human superiority in this period of history.

The public may be under the impression that the Rising Star haul is a bunch of bones which palaeontologists have been piecing together to make up a human skeleton. However, one of the most extraordinary aspects of this discovery, is that the bones are “from neonates to elderly and everything in between, and we have practically every bone in the body,” says Lee. Collectively, between 30 and 60 individuals have been identified, who are certainly of the same species, and this is a “powerful tool for scientists to unlock human processes like growth, difference in sexes, disease and ageing. We have never had an assemblage like this for any other hominin species,” says Berger. “It is therefore an open book,” that allows for research into subtle nuances and possibly behaviour, making this the largest such scientific project in the world, says Berger.

I try again to get Berger to reveal what his latest findings are. There are several mysteries about H naledi that loom large: how exactly did it survive alongside bigger-brained species; how did the skeletons come to be in the caves, some laying on the surface of the ground, unlike other fossil finds; where are its tools, and what were those tools, given that naledi’s hand structure suggests it could use them; did it use fire to light its way into the caves, and what is the significance of the mix of human and non-human traits? I ask if they have answers to any of these questions now, but he demurs. “Have they found more bones, new bones? “Yes to both, but that’s not what it is,” he says coyly. “We have made great advances beyond what we had expected,” he says before again pleading the Fifth, but he does say that the new finds will be fast-tracked as they are not difficult to describe. This, together with two articles presently under peer review, should give the world something to sit up and take notice about.

Homo naledi is the single largest fossil hominin find yet made on the continent of Africa.

Berger says that, for a discipline that had been deemed moribund as recently as 2000, it is now in a glorious era of exploration and discovery. “The last 10 years”, he says, “have produced the most significant fossil finds ever, and have overturned everything we knew”.

The import of Berger’s assertion is colossal, given just some of the momentous fossil finds of the past. In 1856 Neandertal fossils were discovered in western Germany, giving shape to how we saw our early ancestors. The discovery in South Africa of the Taung child (Australopithecus africanus) in 1924 gave the first suggestion that humankind came out of Africa. 3.2-million-year-old Lucy (Australopithecus afarensis) was, when she was found in Ethiopia in 1974, the most complete hominin skeleton of the time. Nearly a decade ago, Australopithecus sediba was deemed by many as the most important hominin discovery ever, when Berger and his colleagues discovered its bones in Malapa Cave at the Cradle of Humankind. Dating back 1.977 million years, it was considered a potential new human ancestor, although debate still rages.

Berger says that technological exploration technologies are driving this age of discovery. Everything from investigative tech, such as satellite mapping technology, to Synchrotron-based imaging techniques which identify previously unseen anatomy preserved in fossils. He notes that as recently as two years ago the augmented virtual reality tech which they used in caves, and which cost hundreds of thousands of dollars, has been overtaken by what can be done on an iPhone. “This is the real experience of exploration and discovery, and it allows us to investigate spaces more completely. But there is nothing that supplants the power of having humans accompanying that tech. We have yet to replicate the human brain”.

While his historic findings are exciting in themselves, Berger says they are important because they allow us to understand ourselves as humans.

“We have known as humans for thousands of years that it is critical to understand humankind’s place on this planet, even before we understand the essence of who we are, and we do this by looking where we have come from. This fulfils an obligation of wisdom. You cannot hope to look at rest of the world and understand it without understanding yourself. There is no more important question, especially in the light of some of the big questions which face us in relation to climate change.

“We have floundered about observing the world without understanding truly that we are part of this system. We have an evolutionary history as complex as any other animal but likely no more so. That is the beauty that naledi brings to the table. It takes away this human arrogance which has been much of the cause of our destructive behaviour, this right to ownership, this right to destruction, the territorial nature of our behaviour towards this planet. We have seen ourselves as superior, as special, we’ve told ourselves a special origins story that isn’t true. What can be more important than taking yourself off that pedestal and removing some of the destructive behaviours that manifest in humans.

“Naledi has affected me fundamentally. I used to think of myself as a cold white lab coat scientist. But you suddenly realise that there are bigger things about our origin story and our place in nature that we’ve missed and these questions of humankind’s desire to separate themselves from nature is a dangerous, damaging thing. And the stories we’ve told ourselves, whether they be religious, or political, and the laws we make giving us rights, are based upon a flawed assumption that we are unique, and were unique, and we’re the highest order of evolution in both mind and body. It’s not true.”

How has Berger’s thinking changed about the human trajectory? “If we had been having this conversation 12 years ago, I would probably have been talking about the purebred nature of humans as a singular African species out of Africa that conquers the rest of the world, driving everything to extinction. Whereas we now know that that is not true. We are a curr, a mutt, a series of chance interactions and genetic introgressions with everything that was out there. We are just this amalgamation of encounters that occurred as populations of different species expanded and contracted, met each other, shared DNA, and that’s what we are today. We’re no purebred destiny that came marching out of Africa. These are critical discoveries.

“We now sit in the greatest age of exploration. We’re making these kinds of discoveries about our origins, molecular, archaeological and so on, and we’re discovering more about the morphology of these ancient relatives and understanding more in understanding that we knew less.

I ask what are the most impactful discoveries of this time? “They are the next ones that are going to be made,” replies Berger.

“They’re the ones we haven’t made yet, because it’s become profoundly clear to me that we know very, very little. What we need to do is inspire every science to understand that, if a science like mine, which thought it had everything figured out 15, 20 years ago, but that in fact we knew nothing, that has to be true for other science, tenfold,” says Berger.

Berger comes across as irrepressibly optimistic, but how does he rate the chances of human survival in the light of the apocalyptic thinking that seems to prevail in the face of climate change, among others.

“I don’t like your question,” he answers. “This is exactly what I’m fighting against: the idea of ‘is it all about us’? Do you really want to make that question all about us? Humans will survive. That’s the thing we are. We have millions of years of history in our lineage of survivors. Tons of extinction along the way too, but we are the process of that survivor. What has changed in the past couple of thousands of years is that humans have manifested that ability to use the infinite toolkit and to be the most adaptable animal perhaps that we’ve ever observed, and we’ve used it destructively, to wipe out not only other bipedal species, and drive them or breed them to extinction, but we’re doing that to the whole planet, and I think that’s shocking. That’s why we have to go back to that understanding that we are part of this system.

“Yeah, if you want to live on a world with five grasses and four different species in a barren wasteland of a planet, there’ll be humans on that. But that’s not the message we’re trying to get to the world. We have to remove this innate separation that humans have in their perception of nature. Perhaps we’ve been going about it the wrong way. We’re not clearly seeing the solutions and discoveries which must be in front of us. But it is also about changing humans’ perceptions. There are too many of us. What we need to do is force humans to recognise they are part of this natural system and understand that there’s not some God-given right to destruction and ownership for humans. That is a falsehood.”

So what is to be done? First, the messaging needs to improve. “I don’t think climate scientists and others do enough of that messaging. They tend to always couch it in human survival. I think that’s got to change. It isn’t all about us.

Further, “we have discovered more remains of hominins in the last six years than in the entire history prior to that on the continent of Africa. It’s transforming our understanding in ways I can’t even talk about because I don’t know all the ways. That’s the messaging for all scientists. Have they not thought that they have got the answers but are staring at other solutions and discoveries that are right in front of them? Sometimes we stop looking when we think we know the end of the story, and that is part of the message. If we talk about doom and gloom, well, that’s where my field was 20 years ago. ‘It’s all over. Nothing left to find. Let’s stop funding exploration. We know the story anyway’. And that’s a depressing place to be.”

“One thing is clear: you can’t stop exploring. You think you know where this thing is going, what the trajectory is, that it’s doom and gloom. No, you don’t. Take it from one scientist to another: no you don’t. Keep exploring. There are discoveries right in front of you.”

Meanwhile, the world awaits news of Berger’s latest discoveries from the Rising Star cave. Perhaps a tool used by Homo naledi?

Images courtesy of Wits University: https://www.wits.ac.za/homonaledi/

Berger is the Phillip Tobias Chair in Palaeoanthropology at the University of the Witwatersrand, and a National Geographic Explorer at Large. He has been adviser to the Global Young Academy, the Jane Goodall Institute South Africa, and has chaired the Fulbright Commission. He won the first National Geographic Society Research and Exploration Prize in 1997. In 2016, he was named the Rolex National Geographic Explorer of the Year and included in Time magazine’s list of the world’s 100 Most Influential People.

The 11th Oppenheimer Research Conference takes place between 5th and 7th October 2022 in Midrand, Johannesburg. The Oppenheimer Research Conference (ORC) showcases cutting-edge, innovative scientific research and provides a platform to foster engagement and dialogue. By so doing, it contributes African voices into global conversations on environment and sustainability. The 2022 conference is fully booked, but there will be some livestreaming. Keep an eye on the Oppenheimer Generations Research and Conservation website for more details.

Vulture survival, poaching threats, and hope from the skies

Pangolins are elusive and heavily trafficked. At Tswalu, researchers are working to uncover their secrets and aid conservation.

Declining Sparrow-Weavers may threaten other birds that rely on their old nests for shelter.

Wakefield cattle - Michelle Tedder.jpg