Journalists and scientists often speak at cross purposes – even a “different language”. Are there ways for them to understand each other better in the interests of the public good?

Amid the gutting of newsrooms, and what is now being called a post-truth world, there is greater onus on scientists to help keep the public well informed.

But communicating science presents inherent difficulties due to its complexities. At the same time, contemporary media, largely through social media, has become characterized by fake news. This has eroded trust between the science fraternity and journalists.

So says leading science communicator, Rob Inglis, who facilitated last week’s Tipping Points webinar hosted by Oppenheimer Generations Research & Conservation.

It was the 10th in a series and the first of 2023. The Tipping Points meetings provide a platform to discuss issues affecting development and the environment in Africa.

Entitled “Science and media: Mind the Gap!”, the webinar, brought together media people, researchers, and others to mull over how science communication could be more effective and far reaching.

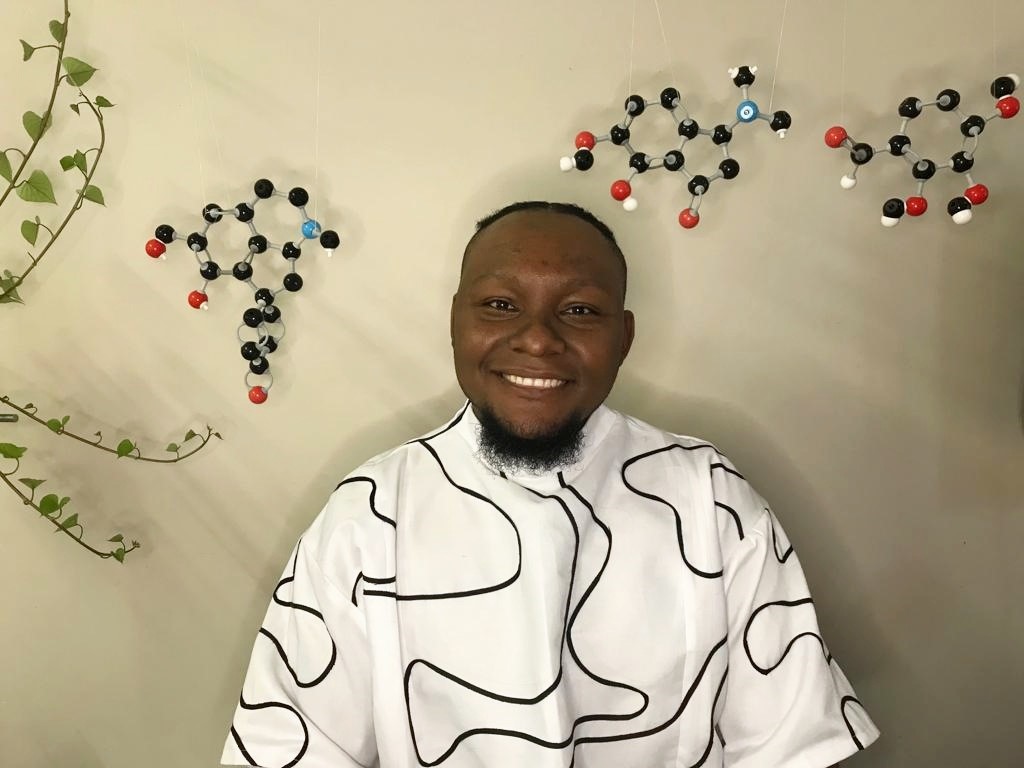

The panellists were award-winning environmental journalist, Elise Tempelhoff and Dr Nehemiah Latolla, a Phyto chemist at Nelson Mandela University.

Latolla last year won the FameLab International Competition. Dubbed the “Pop Idols of Science” it is intended to inspire and develop young scientists and engineers to engage with the public. His award-winning FameLab presentation provides insight into using indigenous medicinal plants to treat diabetes.

Facilitating the discussions, Inglis spoke about scientists and journalists having very different priorities and how, in a sense, they spoke a “different language”. Yet they needed to find ways to work together to “get good science out to the public”.

He asked Tempelhoff about the difficulties she faced dealing with scientists as well as deadline pressures and other headaches of her job.

“You are always fighting with someone,” said Tempelhoff, of the contested terrain her reporting traverses. (She covers everything from conservation and the endangered wildlife trade, to environmental degradation, and oil and gas exploration.)

The former Netwerk24 staff journalist turned freelancer, seemed cheerfully resigned to the adversarial nature of her work. But told of how tight daily newspaper deadlines, the demise of in-house, specialist beat reporters and the competing demands of a “torrent” of stories meant there was no time for pouring over lengthy research papers. She limited herself to reading in full only the executive summary and the conclusion; the rest of the paper she scanned.

But the burden of care could not be escaped and Tempelhoff stressed it was vital science reporters understood what they were writing about; they should never view themselves merely as a conduit.

“I am not just communicating; I must be critical. I can’t just copy and paste and just translate (into Afrikaans). I have to look at the different sides of the story,” she said. To help her with this task, particularly when working against the clock, she prized scientists who could send her explanations of their work in terms so lucid that, Grade 10 pupils could grasp it.

Inglis wanted to know about Tempelhoff’s fact-checking routines.

“Do you give your interviewees a chance to look at the material? A lot of scientists feel they were misrepresented in the final piece,” he said, referring to the changes that happened in the news and copy-editing processes, after a reporter has filed a story.

Tempelhoff said she does not usually share her stories before publication.

“I will talk a lot (with the interviewee) and make sure… I am very careful. If it is a very difficult story, and I am not sure, I will send it to the scientists,” she said, but noted that some academics exceeded fact-checking and began fiddling with the semantics of a story.

She said building trust was important and off-the-record briefs must remain sacred. However, journalists should find ways to work background – which provided valuable context – into their stories, “without compromising the trust”.

She wondered why South Africa’s climate scientists were “very quiet at the moment”, instead of sharing their work and questioned why journalists were sometimes excluded from important scientific get-togethers despite a clear public interest. Here she mentioned an annual week-long meeting of researchers at the Kruger National Park. “We are not allowed there. We need to know what is going on. Sometimes we don’t even know the scientists who are working there,” she said.

She said scientists also needed to appreciate that journalists were always on the lookout for science stories that people could personally relate to. “How will the drug improve my life? Why does it matter? Will the research improve the human condition”.

“Why do scientists do science?” Tempelhoff asked, grappling with a question from Inglis about how communicators could make a human connection in their writing about sometimes very technical science. “Don’t they do it to improve the human condition? And if something can improve the human condition you write stories about that . . . stories that grab the imaginations of a reader.”

Although there was plenty of research that fitted this bill, “scientists don’t know who to contact”, she said.

The solution lay partly in scientists getting to know specialist journalists better. They should send news and tip-off to the specialists directly, she said, rather than to harried news editors and managers, where “it disappears in a big bin, a big email inbox”.

Similarly, Tempelhoff felt journalists must get over any qualms they might have about self-publicity.

She said as much as she loathed self-promotion, it puts her on researchers’ radars. And, with time, as they develop mutual trust, there was a better chance of important findings reaching the public.

To improve the odds of this happening further, Tempelhoff suggested scientists simplify their communication.

Latolla agreed but said this was often easier said than done.

“We are trained to make the findings speak for themselves” and to communicate “without bias and personal opinion”. He appreciated this often fitted poorly with the media’s efforts to “tell the human story”.

Then there was the problem of scale and context.

“Science looks at small areas of a larger context. But the media is interested in the context. The media goes straight to the ‘so-what question’, which puts scientists in a tight position,” said Latolla.

Scientists could appear frustratingly diffident (from a media perspective) too. But Latolla said they spoke about “we”, rather than “I” for good reason: they were wary of claiming the credit for what was often a team effort.

Certainly, scientists were well aware of the possible bigger implications of their research but were anxious “not to overstate or oversell”. With experience they came to be mindful of their own ignorance, having learnt that everything “could change tomorrow based on a small factor” and they may have to retract.

On the other hand, he quipped that, “We (researchers) have no problem stating implications when applying for funding. We should sit back and think of that!”

Latolla also acknowledged that some scientists found dealing with necessarily interrogative journalists daunting. This was especially true of early-career scientists who worried about their own plausibility.

Drawing on his own observations of science communication during the Covid-19 pandemic, Latolla said a “great deal of misinformation” arose because “scientists were not effective in telling their stories” and this had left the public podium to politicians.

A relatively recent convert to Twitter, Latolla spoke about how the medium was useful for scientists to get their messages to the public. It also created networks of researchers and others, including journalists, who followed particular subjects.

Inglis pointed out “science is changing, and knowledge is changing” and wanted to know how scientists and journalists should communicate to a public that sought certainty.

He also spoke about how scientists took pains to guard against “overstatement”. Research or medicine approval processes, for example, take years but journalists focus on the immediate.

Latolla said a research project was generally focused on a small part of a very complex system. Other research in different areas might expose small contradictions, “but that’s fine”.

“We need to move out of the idea of wanting certainty,” he said, “As we learnt from the Covid experience. We need to become comfortable with uncertainty.”

He suggested communicators take a nuanced line: “At this point we know this. This might change but these are the measures we are taking now.”

Before Covid many in the public were ignorant of the systems of pre-trials and trials that preceded the roll-out of medicine. And in the context of his own work, developing treatments for diabetes, people – journalists included – were frequently unaware of the money that was required and the bureaucracy that must first be surmounted before you take a plant with medicinal properties and put it on a pharmacy shelf.

“We can do a better job, maybe, talking about the process,” he said.

And a lot of work needed to be done by the media and scientists to build trust, Latolla added. “Trust is the key going forward to a better engagement.” – Roving Reporters.

- The monthly Tipping Points webinars are covered by a team of young Roving Reporters enrolled on an environmental journalism training project supported by Jive Media Africa.

The next Tipping Points webinar on March 30 will consider what makes a good proposal for young scientists who want to apply for the annual $150,000 Jennifer Ward Oppenheimer (JWO) research grant. The grant is awarded to an early career scientist whose research facilitates solutions to African challenges with a strong link to biodiversity and conservation.

- Unveiling the past to shape the future - April 8, 2025

- Mixed report for Nature COP - December 18, 2024

- Hacks vs boffins – bridging the divide - March 9, 2023

Additional News

Pangolins are elusive and heavily trafficked. At Tswalu, researchers are working to uncover their secrets and aid conservation.

Declining Sparrow-Weavers may threaten other birds that rely on their old nests for shelter.