Four in every five of us worldwide depend on medicinal plants for their primary healthcare. But are Africa’s traditional healers, the source of many of these cures, benefiting?

Africa’s indigenous forests are a fabulous treasure trove – a cornucopia of foodstuffs, seed varieties and medicines, a bulwark against climate change and environmental degradation. It’s a shame then that so few of the continent’s people are getting a fair share of this natural bounty.

There is a vast amount of medicinal wealth found in Africa’s forests, but in the absence of formal intellectual property rights, traditional healers can count themselves lucky if they get crumbs from the big pharma table for any traditional cures developed into drugs. None of which is to say healers make it easy for those who wish to help them…

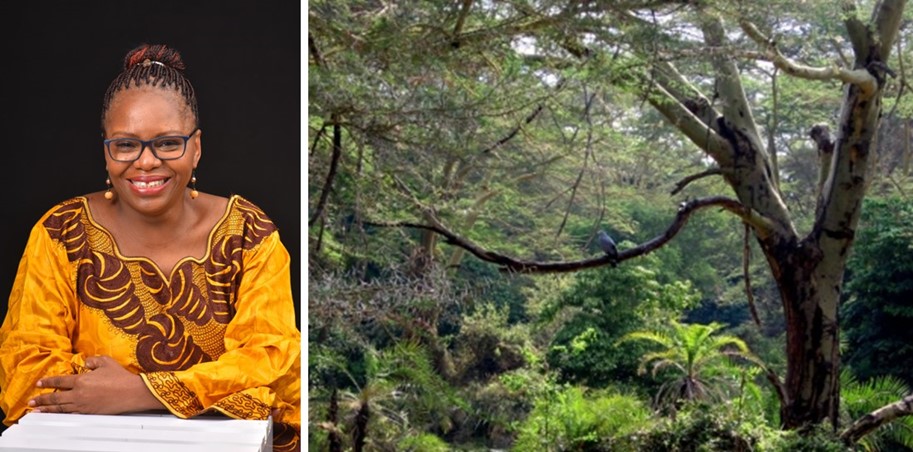

A bit like a big chunk of beautiful African mahogany, the problem is a knotty one. And just why it’s so complicated (and a few possible solutions) was the subject of a talk Kenyan forest scientist Dr Doris Mutta gave at the 12th annual Oppenheimer Research Conference, in Midrand from 4 to 6 October.

Mutta notes that while forests provide Africa with a huge harvest, investment in forests and tree-based systems have not matched their importance.

“The sector is marginalised… Preference is given to other sectors. Forest conversion to other land uses continues unabated, eroding its potential,” says Mutta, whose schoolgirl dreams to become a medical doctor have found expression in her botany related work as a forest scientist.

On the industrial timber front, Mutta quotes an estimate by the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organisation that 79-million cubic-metres of wood was harvested in Africa in 2018. If this amount of wood were to be planked in stacks, one metre high and one metre wide, and lined up end to end, the stockpile of wood would extend over 79,000 kilometres which is nearly double the circumference of the globe. And this figure of 79-million cubic metres of wood is thought to be “a substantial underestimate, due to large-scale illegal felling and trade in many countries,” says Mutta.

Mutta made her conference presentation a week before a Nairobi court suspended Kenyan President William Ruto’s decision to allow logging to resume in state forests after a more than five-year ban.

Ruto had lifted the ban in July, saying this would create jobs and develop sectors of the economy that depend on forest products.

However, the Environment and Land Court on Thursday ruled that the measure was “null and void” due to a lack of public debate on the issue.

Environmentalists have argued that lifting the logging ban, will reverse gains made in recent years to improve Kenya’s tree cover after the moratorium was put in place in 2018. According to this article, deforestation in Kenya rose steeply from the early 1990s up to 5,000 hectares a year by 2010. This had several consequences, including changes in biodiversity, river flows and the microclimate.

In an interview with Roving Reporters, Mutta said, in principle, she would not be opposed to lifting the logging ban, provided it was done right and in line with best forestry practices.

She points out the plantation forests comprise only exotic tree species, mostly pine and cypress, and that the management of plantations and indigenous forests require entirely different approaches.

Sometimes, she says, we get so caught up in the need to preserve our natural world, that we cease to see the trees for the wood, so to speak, and forget the value timber can bring, meeting domestic market needs, providing jobs and growing economies.

This means that commercial forestry must be supported by strong regulations, effective monitoring systems, and follow specified science-based felling cycles.

If it’s legal and sustainable, it’s OK, she says.

“Provided trees are planted and given sufficient time to grow, it makes sense to harvest them,” she says. “And unlike indigenous forests, once the trees of a commercial plantation reach maturity, any added time on the land does not bring value and can lead to a decline in the quality of timber.”

Who profits?

But as to who really profits, is moot, says Mutta.

She is concerned that the forestry business and commercial logging in Africa is not adequately coordinated and regulated, with international private companies sending profits abroad.

“Equity is one of the issues that need to be addressed along with strengthening our laws and institutions to make sure that the benefits remain more in our continent,” she says.

Mutta is also interested in how non-timber forest goods contribute to other sectors including the pharmaceutical industry, biotechnology, cosmetic, and food and beverage industries, and the way indigenous forests are a source of valuable varieties of seeds and food crops found only in Africa.

She notes that the continent has about 640 million hectares of forest or woodlands of one sort or another — from mangroves to Afromontane forests, dryland forests, miombo woods, to the world’s second largest tropical rainforest, in the Congo basin. Together, these cover about one-fifth of Africa’s landmass and represent 16% of the world’s forest cover.

Nearly 250-million people, or one in five Africans, live within 5km of forests, which provide about 20% of their household income and for many, a route out of poverty. And during Covid, and more recently, as war in Ukraine roiled world markets, forests have helped the continent’s people weather global financial storms.

Knowledgeable

Born and bred in Mombasa, Mutta completed a MSc in Botany at the University of British Columbia, Canada, and a PhD in Environmental Studies at the University of Strathclyde, Glasgow, Scotland.

She has 30 years’ experience in research and management of forestry, coastal, and marine ecosystems in Africa and today serves as a senior programme officer at the African Forest Forum. She manages a project, supported by the Swedish government, that seeks to strengthen the management and use of forest ecosystems to aid sustainable development in Africa.

Mutta shares concerns that over the past 15 years, agriculture, livestock grazing, logging, charcoal production, and new settlement has reduced the size of the Mau Forest by a quarter of its previous extent (400 thousand hectares).

Amid this widespread deforestation, Mutta believes traditional healers could play a vital role in protecting Africa’s forests.

Traditional medicine

“I’ve done a lot of research on traditional medicine, indigenous knowledge of medicinal plants and issues of intellectual property rights,” she says.

“People living in or near forests are key players. They know what’s happening in the forest area and they know the value of that forest. They have indigenous knowledge on how to sustainably use the forest… for example, for food and medicine.”

But drawing on traditional knowledge can be hard to do.

“Some of the traditional healers and herbalists don’t tell scientists everything. They hold back some information as a trade secret. They say if I tell you everything, you’ll publish the information and together with prospectors from the north, the wazungu (Swahili for a white person), you will develop modern products and you’ll forget me. You’ll make money and I will remain in poverty,” says Mutta.

She would like to see the development of an intellectual property system that ensures “knowledgeable people in our villages in biodiversity rich areas” feel safe and happy to share their knowledge about natural remedies.

“They need to know that they are contributing to the society and that they will get a fair share of benefits for knowledge that is used and developed,” says Mutta.

Witchcraft Act

Accusations of witchcraft and the threat of punishment under Kenya’s Witchcraft Act are another serious deterrent to traditional healers and herbalists sharing their knowledge. Its amendment in line with the Constitution of Kenya, 2010, is long overdue, says Mutta.

And bridges can be built, says Mutta.

Mutta told of a Kenya Forestry Research Institute project some years ago that secured funding from USAID to bring herbalists together in Malindi on Kenya’s North Coast.

“It was the first time they were brought together in the open. They had always been hiding, but because some of them knew me – I had done my research there – they just came.”

“We organised an exhibition for them and formal certification to show that they belong to a recognised herbal medicine association. This earned their trust,” says Mutta.

One door closes…

Mutta’s interest in the medicinal value of forest plants is not surprising when you consider she comes from a family linked to medics.

Studying medicine was the young Mutta’s dream career, but life had other plans.

In her final year at school, when completing a university application form, a friend suggested she put down forestry as another option.

“I just put it there just for the sake of filling the [application form] space,” says Mutta.

Then, two weeks before her final high school exams, Mutta’s mother passed on.

It was a trying time for her and her final exam marks weren’t good enough for medical school.

“I gave up the idea of going to university, altogether,” says Mutta. But later, she received a letter advising that she had been admitted for a BSc in Forestry at Moi University in Kenya.

She excelled in her studies, graduated in the top five of her class, and won a scholarship to study for a MSc in Botany at the University of British Columbia. Soon she came to realise it was a field that could still let her get her teeth into matters medical through the study of plants.

Game changer

Her second supervisor, Prof Nancy Turner at the University of Victoria, a world renown economic botanist, “really encouraged me,” recalls Mutta. “She held my hand and is the reason I continue to follow economic aspects of my botany work.”

Before taking up her present position with the African Forum, Mutta worked with the United Nations Environment Programme on the Nairobi Convention for the Protection, Management and Development of the Marine and Coastal Environment of the Eastern African Region. Before that she worked for the Kenya Forest Research Institute for 20 years as a research scientist and centre director.

Mutta’s lifelong interest in medicinal plants was inspired by ethnobotanical research she conducted as an undergraduate in Kenya’s Arabuko Sokoke Forest.

“All my project studies had to be conducted in forests,” says Mutta. “I had the exceptional opportunity to work within a community, the Giriama, who I could relate to, and easily communicate with, as they have close links to my own tribe, the Rabai,” says Mutta.

The Arabuko Sokoke Forest is considered one of the most valuable conservation areas in Africa due to its thriving biodiversity. According to the Edge of Existence Programme, it is home to 600 indigenous plant species, 270 species of birds, 261 different kinds of butterflies, and a wide variety of reptiles and amphibians (79 species), and 52 mammal species, including African elephant, the golden-rumped elephant shrew, Ader’s duiker, the Sokoke bushy-tailed Mongoose and the African golden cat.

These forest ecosystems, says Mutta, are a lifeline for villagers who continue to resist plans to explore for gas and oil in the Arabuko Sokoke Forest, and, more recently, proposed titanium mining.

Among several community based conservation initiatives based in the forest are the world-famous Kipepeo Butterfly Project and the Bidii na Kazi women group, both of which generate income for women who breed and sell several species of butterflies, exporting and selling butterfly and moth pupae and other live insects as well as honey and locally produced silk cloth to buyers worldwide.

Mutta believes that projects of this nature, and other similar conservation initiatives, all help counter exploitative practices that are accelerating the rate of deforestation in Africa.

We need to be vigilant if we hope to halt this destruction, says Mutta. This, she adds, requires lots of political good will, and of course, support from those who have depended on these forests for generations – the real custodians of Africa’s bountiful treasures.

Main Photo: The Mau Forest is one of Kenya’s “water towers”, so named because of the role they play in the catchment, storage and natural purification of water. The water that is trapped by, and travels through, these forest catchment areas flows into major rivers and lakes, including the Nile and Lake Victoria, providing direct benefits to millions of people in East Africa, and even beyond. Patrick Sheperd/CIFOR | Flickr

This story was produced with support from Jive Media Africa, the science communication partner to Oppenheimer Generations Research and Conservation.

Author

- Why we must safeguard our forest muthi - October 18, 2023

Additional News

Pangolins are elusive and heavily trafficked. At Tswalu, researchers are working to uncover their secrets and aid conservation.

Declining Sparrow-Weavers may threaten other birds that rely on their old nests for shelter.