Alien species are giving freshwater ecosystems in Africa and beyond a mauling. But a new project, backed by funding from one of the continent’s premier prizes for young researchers, holds hope.

Lion guru Craig Packer reveals how big cats develop a taste for human flesh and why we shouldn’t swallow big hunters’ wild tales.

Sensational tales of Great White Hunters who have killed ‘man-eating’ lions detract from the real experiences of lion attack victims and the reasons why such incidents persist, says world-renowned lion expert, Dr Craig Packer.

In the coastal shrublands of southern Tanzania, villagers face a stark reality: hungry lions deprived of their natural prey. Africa has lost around 90% of lions’ native habitat in the last century to accommodate an expanding human population. This has come at a fatal cost to both humans and lions, says Packer.

Exactly how many people get killed by lions these days — and vice versa — is largely unknown. Internet searches yield conflicting figures, of about a dozen each year. But what is not in doubt is that as human populations expand and lions’ prey dwindles, it is the poorest people — and hungriest lions— that pay the price.

Recently in Kenya, a 60-year-old man nearly died in a struggle with a lioness that was preying on people’s livestock. These often follow a pattern that has been repeated for centuries, says Packer who is currently revisiting decades of research into human-big cat conflict.

For over 40 years, the American ecologist and award-winning author has studied lions in Africa, from the Serengeti to South Africa and the Maasai Mara. He has seen them at their most playful and their most savage.

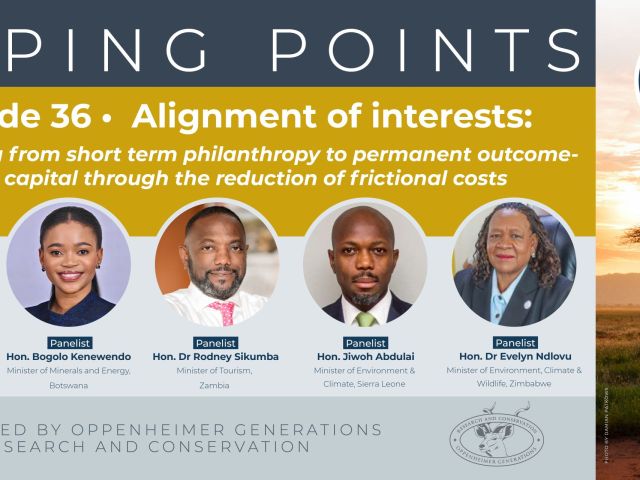

Packer’s findings will be presented at the 12th Oppenheimer Research Conference in Midrand, South Africa, in early October. He will delve into the significant man-eating lion outbreaks in East Africa and south Asia, and draw on similarities with other cases, including the Man Eaters of Kruger which preyed upon Mozambican refugees crossing through Kruger National Park to South Africa illegally. His presentation shall also cover the Man-Eaters of Tsavo, the less well-known Man-Eaters of Sanga who were responsible for the largest known outbreak in Uganda, and the famous man-eating leopards and tigers of Kumaon that were despatched by Jim Corbett in the colonial era in India.

Myths and legends

For over a century, the myth of the “Great White Hunter” has captivated audiences in Europe and North America. Renowned explorers like Dr David Livingstone, while on a mission to eradicate the slave trade and spread Christianity in Africa, spun vivid tales of being attacked by man-eating lions in what is now Zambia and Zimbabwe. Similarly, Colonel John Henry Patterson’s famous book “The Man-Eaters of Tsavo” perpetuated the belief that white men were the only saviours for helpless villagers during the rampant outbreak of man-eaters that occurred during the railway construction from Mombasa to Kampala. But the untold stories of victims, Packer says, are an entirely different narrative.

Survivors’ stories

In the early 2000s, the Tanzanian government sought Packer’s expertise to investigate a major outbreak of man-eating lions in the districts spanning from Dar es Salaam to the Mozambican border. Along with two young researchers, the team interviewed hundreds of lion attack survivors and their families. Their research shed new light on the risks of being attacked by man-eating lions which had largely been overlooked by the ‘white heroes’ who had been called in to eliminate problem lions during the colonial era.

A lifelong pursuit

Packer’s lifelong study of animal behaviour began in 1972 as an undergraduate field assistant for Jane Goodall at Gombe National Park in Tanzania. Instead of focusing on chimpanzees like Goodall, he studied olive baboons — looking at their family dynamics and social connections. Packer had intended to come to Africa for just a few months and return to the US for medical school, but he got so enthralled in watching animals and being in Africa, that he stayed. “I guess I got what they call Le mal d’Afrique — the obsession for Africa,” he jokes.

After completing his doctorate in biology at the University of Sussex, Packer found himself drawn back to Africa, this time to the vast plains of the Serengeti, where he immersed himself in the complex lives of lions for the next four decades. Initially, he explored questions like ‘why do lions live in groups?’ and ‘why do they have manes?’ But a devastating disease epidemic in 1994 claimed one-third of the Serengeti lion population and shifted Packers focus to conservation.

“Here was a population of lions in the middle of one of the best protected national parks in Africa. And yet so many of them could die,” Packer says. It turned out to be a disease epidemic that was the result of poverty. In rural communities near the Serengeti, scarce veterinary services meant domestic dogs were unvaccinated against lethal diseases like rabies and distemper which, in turn, infected local lions. Packer’s team started working in villages outside the Serengeti, vaccinating people’s dogs but soon after the disease outbreak had been addressed, a new challenge threatening human and lion populations became too big to ignore – habitat loss and the resulting loss of lions’ natural prey.

Easy pickings

When Packer went to investigate the outbreak of man-eating lions in southern Tanzania, he was shocked to see how vulnerable people were to lion attacks: most victims of the attacks were peasant farmers surviving on a single crop a year. To safeguard their crops from bushpigs, which had become the primary food source for the remaining lions, farmers slept in their fields making them easy targets for attacks. “Once the lions developed a taste for human flesh, they even started raiding villages,” says Packer.

In an article titled Rational Fear, published in 2009, Packer recounts some of the horrific cases from his team’s interviews: “Lions dig through thatched roofs and drag elderly people out of bed; they pluck small children from the breasts of their nursing mothers… one woman lost her husband and parents in two separate attacks several months apart.”

In revisiting earlier man-eating lion outbreaks in Njombe, Tanzania, Packers challenges claims by the late British game warden George Rushby that three generations of lions had killed as many as 1500 people from 1932 to 1947.

He argues that this is an inflated figure, complicated by the simultaneous murder hundreds of people by “lion-men” or “spirit lions” – assassins hired to kill enemies and disguise these deaths as lion attacks “In some cases, they used metal hooks and curved knives to disembowel the victim to make it look like they had been eaten by lions,” says Packer.

“So, there was a mixture of real lion attacks with a fair number of murders,” says Packer.

Everchanging relationships

Packers’ research shows that problems with big cats usually result from a loss of prey caused by a diverse range of factors.

He states that while the lion attack outbreak in Tsavo in the late 1890s was triggered by an outbreak of rinderpest that devastated lion’s natural prey, in Njombe agricultural expansion destroyed a lot of the natural habitat resulting in a sharp decline in the numbers of wild animals for lions to eat, says Packer.

He also draws a parallel with what happened in India following outbreaks of cholera and Spanish flu. During those epidemics, peoples’ bodies were thrown into valleys, as there were too many victims to observe the usual rites of cremation. “The corpses attracted leopards and tigers and inspired the big cats to see people as food,” says Packer.

The relationships people have with lions also vary considerably from region to region.

Retaliatory killings

For example, in the savanna habitats of Kenya and northern Tanzania, lions often face retaliatory killings by Maasai and other pastoral communities in response to livestock losses. This, paired with a culture of young warriors spearing lions to prove their courage has led lions in these areas to be more fearful of humans and so less likely to become man-eaters than in the subsistence-agricultural areas of southern Tanzania. In Botswana and Namibia, the hunter-gatherer Khoisan communities also view lions as a helpful way of finding food sources. They have been known to chase off entire prides of feeding lions in order to get freshy killed antelope. “In my experience with the Khoisan, the attitude towards lions is one of admiration and respect,” says Packer.

Drastic measures

To put an end to the 21st century outbreak of man-eating lions in southern Tanzania, local people resorted to a drastic measure: poison. Packer recalls a notable incident from 2004 when an elderly woman disappeared after visiting a long-drop (pit latrine) during the night. Her husband discovered her half-eaten remains and instead of burying her, he laced her corpse with rat poison, successfully eliminating the responsible lion. This method caught on with other villagers poisoning half-eaten bush pig carcasses and the remains of slaughtered goats. “Without guns for protection, they felt helpless,” Packer says. “But you can get rat poison from any village shop for just a few cents.”

While this approach stopped the last major outbreak in Tanzania, it isn’t the ideal solution, says Packer. Besides eliminating an endangered top carnivore, poisoned carcasses are causing massive harm to vulture populations and many other scavengers.

So, finding environmentally friendly alternatives to curb human-wildlife conflict is a key focus of the Lion Center which Packer founded at the University of Minnesota in 1986. It aims to advance new evidence-based approaches to lion conservation that balance the needs of wildlife and human communities.

Packer remains optimistic that lion numbers will remain stable or even increase in the next dozen years as lion conservationists work to protect them: “We are learning from the success stories as well as the failures.” In some regions, simple measures like building walls or fences between wildlife and people, as has long been employed in South Africa, have proven effective solutions. But in many East African parks, where wildlife migrates beyond protected areas, barriers are not viable. Here, the focus has been on preserving the largescale movements of migratory herbivores, but outside the protected areas, people keep livestock which are easy prey for lions.

“Today, the people who suffer the most from being around lions are those whose livelihoods depend on livestock,” says Packer. If you keep cattle near wildlife areas, then lions are a threat to your livelihood. And it’s getting worse as pastoralist communities are forced to keep their stock closer and closer to wildlife areas as the rest of the landscape is converted to agriculture – this leads to increased livestock attacks and retaliatory killings of lions, he explains.

Urban encroachment

Urban encroachment on wildlife areas in Kenya, is also becoming a problem, says Packer. Recently, residents of Nairobi recorded CCTV footage of an emaciated lioness walking through a residential area near Nairobi National Park. In nearby Kitengela, a built-up area that was once part of the dispersal corridor for the wildebeest and zebra from Nairobi Park, people witnessed zebra walking along a road through the town.

Many other dispersal corridors in East Africa are being similarly cut off, resulting in greater opportunities for lions to come into contact with pedestrians and pastoralists. The worst of the “man-eating” outbreaks may well be over as the offending animals will almost certainly be despatched more quickly than ever before. “But remember,” Packer cautions, “the problem isn’t with the lions – they are just doing what lions have always done – the problem is with us.”

Main image: In the Okavanga Delta lions thrive. There is an abundance of buffalo and other animals to prey upon. But in many other parts of Africa, native habitat loss has tragic consequences both for people and the big cats. Photo: Hanspeter Baumeler.

In this podcast, Dr Craig Packer talks about the vision behind his work on lion conservation.

This story was co-authored by Caroline Rothery, a freelance journalist and Program Assistant at the Earth Journalism Network, and Steve Mokaya, a biodiversity reporter at The Standard Group in Nairobi, Kenya, with additional reporting from Fred Kockott. The story forms part of Roving Reporters Game Changers series produced with support from science communication specialists, Jive Media Africa.

This story was first published in the Daily Maverick on 29 August.

Author

- Lions and rural communities in a life-or-death battle for survival - August 31, 2023

- Why we must safeguard our forest muthi - October 18, 2023

Additional News

Alien species are giving freshwater ecosystems in Africa and beyond a mauling. But a new project, backed by funding from one of the continent’s premier prizes for young researchers, holds hope.

Alien species are giving freshwater ecosystems in Africa and beyond a mauling. But a new project, backed by funding from one of the continent’s premier prizes for young researchers, holds hope.